Between Fondamenta Nove and Murano lies the Island of San Michele: a place known mainly because here is the monumental cemetery of the city. This strip of land, far from the most crowded calli, allows you to see Venice from a different point of view, not only geographically, but also historically and culturally.

The history of the island

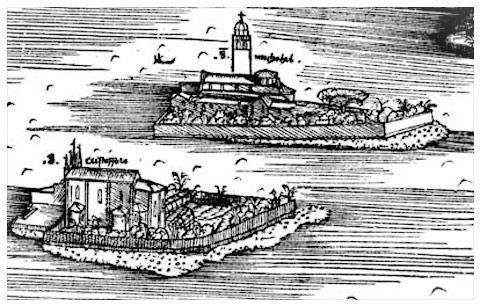

This island in the Venetian Lagoon has a curious origin, beacause it has not always been as we see it today. Originally there were two islands here, San Michele and San Cristoforo della Pace.

In 1804, with the edict of Saint-Cloud, the burials of the dead were no longer possible near and inside the churches. So in 1806 it was considered urgent to find a solution also in Venice. And so, after a couple of hypotheses, it was Napoleon Bonaparte himself who chose the island of San Cristoforo to host the city cemetery. Shortly after the need to expand it, the nearby island of San Michele was thought of. The solution that was found, however, involved a particular work: the rio that divided the two islands was buried in order to form a single one.

Today if you look in any map for the island of San Cristoforo della Pace you will not find it: once incorporated in San Michele, it lost its identity. This does not mean, however, that it is not important to know its history. In fact, it is not only closely connected to the island of San Michele, but also to the whole city of Venice.

San Cristoforo della Pace, in the 14th century, was the place chosen to place a windmill. This strip of land then housed a women's hospice and later a convent of Brigidini, later run by the Augustinians.

Then chosen as the place of Christian burials, the commission for the construction of the cemetery was given to Giannantonio Selva and in May 1813 was completed. On 28 June of the same year the chapel and the cemetery were blessed.

The history of St. Christopher of Peace and his cemetery was interrupted in the first half of the 19th century. The space soon became insufficient and the only solution was to occupy the island of San Michele, which already housed an important Camaldolese monastery.

Today San Cristoforo remains the historical testimony of a disappeared past, which can only be remembered thanks to memory and documents.

The church of San Michele

Tradition tells that the history of the Island of San Michele began in the 10th century, when a church dedicated to the Archangel Michael was built, commissioned by the Briosa and Brustolana families.

It is also said that in the past it was called Cavana de Muran because it was used as a shelter for boats from the nearby island of Murano.

Legend has it that the founder of the Camaldolesi, Saint Romualdo, went here. Whether this is true or not, what is certain is that the bishops of Torcello and San Pietro in Castello in 1212 gave the present church in concession to the Camaldolese order. This church was not only renovated, but a monastery was also built next to it.

In the second half of the 15th century, the architect Mauro Codussi, an important name in Venice, designer of prestigious buildings such as the church of Santa Maria Formosa and Ca' Vendramin Calergi, today the Venice Casino) was given the task of rebuilding the entire complex. Built between 1469 and 1479, the church of San Michele is considered the first Renaissance church in Venice.

During the 16th century the large cloister, the guest quarters, the Emiliani chapel and the cavana were built. In the Napoleonic age, however, things changed completely with the decision to dissolve the present community and carry out the confiscation of property. With the subsequent arrival of the Austrians instead, the structure was radically converted into a political prison that saw locked here, among others, the writer, poet and patriot Silvio Pellico.

The façade of the church of St. Michael on the island, also known as St. Michael of Murano because of its proximity to it, as we can see it today, is made of Istrian stone. Tripartite, it is freely inspired by the Malatesta temple designed by Leon Battista Alberti in Rimini. The lower level of the façade is characterised by smooth rustication, while the upper level is noteworthy because here there is a large oculus around which there are four polychrome marble discs. To surmount this second level, there is a curved pediment with the sides connected by two low-bending wings.

Finally, visible on the façade of the church is the inscription "Domus mea domus orationis" taken from the Gospel of Matthew 21,13.

The interior is divided into three naves by round arches, supported by columns. The coffered ceiling is embellished in the central part by a carved and golden rose, clearly visible on the blue background.

If one subtracts from the plan the space of the vestibule, on the side of the entrance and that of the presbytery with the domes, one can say that the church has a perfectly square central body.

Also interesting is the history of the Emiliani Chapel, recognizable to the eye of the visitor who approaches the island because it is placed beside the façade of the church. In 1427 the noblewoman Margherita Vitturi left a substantial sum of money to the Procuratori di San Marco in order to build a place of worship in memory of her late husband Giambattista Emiliani and to dedicate it to Santa Maria Annunziata. The project was carried out almost a century after the woman's death in 1455. The architect who took charge of the work was Guglielmo de' Grigi called the Bergamasco who finished the chapel in 1543. From the beginning, however, the chapel had structural problems and so the famous Jacopo Sansovino was involved in its restoration between 1560 and 1562. Emiliani Chapel is a refined construction with a hexagonal plan and covered by a dome in white Istrian stone. Inside there are three small altars, each decorated with three marble altarpieces sculpted by Giovanni Battista da Carona and representing respectively the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Magi and the Adoration of the Shepherds. Outside, two statues in Istrian stone represent St. Margaret and St. John the Baptist. These are also works by Giovanni Battista da Carona himself.

The cemetery

San Michele is certainly best known for its cemetery. And it is not strange the interest of tourists in visiting it, since it houses the remains of many famous people.

In 1810, by Napoleon's decree, the Camaldolese monastery that stood in San Michele was suppressed and the island became property of the State, which in turn sold it to the Municipality in order to join it to San Cristoforo.

The first burials in San Michele began in 1826 and once the two islands were united, in 1843 a competition was held for the stylistic unification of the complex.

Lorenzo Urbani was the winner, but the work was stopped due to the lack of the necessary money. So in 1858 a new competition was announced, this time won by Annibale Forcellini from Treviso. The cemetery was thus built, although with some modifications compared to the initial project, between 1870 and 1876. In the course of time, a restoration work worthy of note is certainly that of 1998 by the famous architect David Chiepperfield. Also in this case a competition had been announced, this time with the aim of undertaking the work of extending the cemetery.

The cemetery of San Michele has a simple and essential structure, with a Greek cross plan, a perimeter of solid red bricks, in turn circumscribed by Istrian stone.

Until 1950, the entrance was possible from the side of the Fondamenta Nove and every year for the recurrence of the dead, in November, a bridge of boats, similar to the one built for the festivities of the Redentore and Madonna della Salute was built to join the Fondamenta with San Michele. A custom that was interrupted for years, until 2019, when the ancient tradition was restored and, as was to be expected, found the appreciation of the citizens.

Today, coming down from the pier, you can enter the cemetery through a side door that leads to the Chapel of San Rocco, in turn surrounded by 30 smaller chapels. The ancient area thus joins the modern one and walking along the cypress-lined avenue, you arrive at the church of San Cristoforo, built by Annibale Forcellini himself with alterations by Angelo Davanzo and mosaics, inside, by Antonio Castman.

The two cloisters are noteworthy. The small one just after the entrance portal is in Gothic style, with an irregular plan and a well in the centre. The large cloister was built by Giovanni Buora and has three sides enclosing the adjacent magnolia garden.

Inside the cemetery is divided into three areas, depending on the religious denomination: Catholic, Orthodox and Evangelical. A part reserved for the Jewish religion is missing because there is a cemetery dedicated to the Lido.

Famous burials in San Michele

Many famous names can be read on the tombstones by visiting the cemetery. Here you can find characters linked to the history of the town, but also to the world of art, music, entertainment and sport. Men and women, Venetian and not, who have chosen the city of Venice as their last resting place.

Here are some of them.

Igor' Fëdorovič Stravinsky, who in his lifetime had expressed the wish to be buried in Venice next to the tomb of Sergei Djagilev, his old collaborator.

Luigi Nono, composer, but also writer and politician.

Cesco Baseggio, famous actor of many operas of the Venetian dialectal theatre.

The actress Lauretta Masiero, for years a well-known face in theatre, cinema and television.

The painter and engraver Emilio Vedova, buried in the orthodox sector of the cemetery.

The sculptor Luigi Zandomeneghi, author with his son Pietro of the beautiful funeral monument of Tiziano in the church of S.Maria Gloriosa dei Frari.

Christian Doppler, Austrian mathematician and physicist. Famous for having his theories then became famous under the name of "Doppler effect".

Ezra Pound, poet, essayist and translator born in the United States, but lived most of his life in Italy.

Helenio Herrera, Argentinean footballer and considered one of the best coaches ever. Today he is buried in the Orthodox sector of the cemetery of what had become his city in the last years of his life.

Alessandro Poerio patriot and Neapolitan poet, seriously wounded in Mestre during the Sortita di Forte Marghera during the moti of 1848.

Gino Allegri, Venetian aviator and soldier who took part in D'Annunzio's flight over Vienna and was decorated with the gold medal for military valour in 1921, three years after his death.

Giacinto Gallina, playwright considered Carlo Goldoni's heir.

Sergej Diaghilew, choreographer of the "ballets russes".

The island of San Michele is a little place far from the chaos of the calli, but close enough to Venice to be an integral part of the city.

Visiting it is certainly an interesting experience from a historical and cultural point of view, but remember that it is still a sacred place. Those who include this stop on the Venetian itinerary must always remember to enter it with the greatest respect.

Lascia un commento