It's Day 3 in Venice77 and the first Italian film in competition arrives at the Lido. It is Padrenostro by Claudio Noce starring the usual extraordinary Pierfrancesco Favino, hyper accustomed to his admirable and unreachable performances (one wonders if he is human!), and the little Mattia Garaci.

The sensational news is that the film, although highly anticipated, has not convinced either audience or critics.

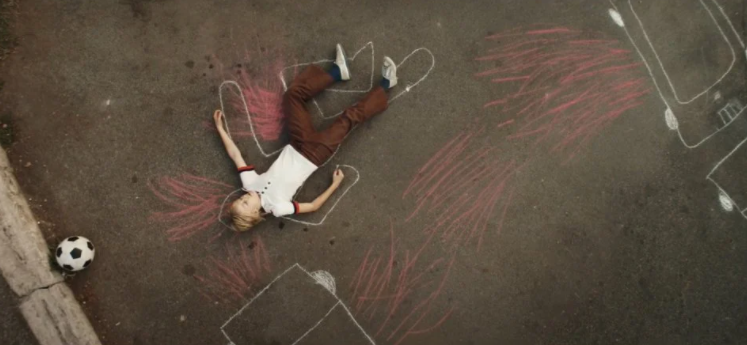

But let's go step by step, starting from the synopsis. We are in the Rome of 1976 when the little Valerio (Mattia Garaci) finds himself together with his mother to assist to the attack of his father, the vice manager Alfonso Noce, on the side of Nuclei Armati Proletari. In the crime loses the life an agent of the escort, while Alfonso remains seriously injured. And from that moment that the Noce family finds itself to reckon with the fear and the feeling of vulnerability that inevitably undermine the stability and serenity that had always connoted them, forcing them also to leave for a while the capital to Calabria. In this moment of great lability, little Valerio happens to know Christian, a little older boy, with a not easy character, rebellious and brazen, a sort of Collodian Lucifer who will somehow change his life, but in the narrative will be revealed only as a "narrative expedient".

Here, what was imagined before the screening was certainly not expected: Padrenostro is not a film about the difficult Years of Lead that Italy experienced in the twentieth century. It is not an autobiographical film, even if it is true that the narrative is inspired by the real life of the director, son of the deputy manager Noce, who at the time of the crime I was just over a year old. It is not a reconstruction of the attack, nor is it the narration of an ideological clash of victims against culprits. Through the cinematographic transposition of the heroic figure of his father, the director wants to trace the contours "of an entire generation of men for whom emotions were perceived only as weakness and forced to be disguised as silence". But it is above all a film that descends to the height of a child's gaze, "on a generation of invisible children, wrapped in the smoke of adults' cigarettes," continued Noce, on the relationship between father and son, which is perpetually hovering between the loving and present father and the absent one who, because of work, is unable to return home, who misses important appointments such as the Sunday morning game: a father figure that is never fully delineated, who appears and disappears in the film as in the life of little Valerio. For Pierfrancesco Favino, who has been in one of the most acute phases of his entire career for some years now, "The political message of this film is to tell the story of his childhood in those years. When Claudio explained the project to me over a cup of coffee, I immediately agreed to help him because I recognized in his subject matter a smell, a taste, silences that I also experienced as a child with my father. We fifty years old today are the generation that has been surrounded by those political events, that has suffered that reality. We were put in a corner, we were prevented from raising a hand. And we rarely put the accent on those children there, who were put to bed and afterwards it was as if they no longer existed when we got up and looked around the corner at what our parents were doing in the living room with their friends".

The centrality of the film lies in the evolution of the figure of Valerio, who most of all suffers the shock of what happened, and like a "game" he goes in search of details to arrive at a reconstruction, a truth about what he experienced: an attempt to express fear? From here the film moves continuously, poised between reality and fiction, between concrete space and psychology, between a more solid and involving Roman part and the calabrian part that becomes cumbersome to the point of forcing: these are dualisms that take the balance away from the narrative, that disorient the viewer in the vision, because after all we are used to flat stories, that slide along the film without great virtuosity.

The film is therefore confused in the continuous attempt to fuse together the psychological influence that brings trauma and flexibility of childhood. A fusion that twists into a disorienting initial vertigo, when the peaceful life of the Noce family is seen by the eyes of the father from above: an attempt to seal a family security that will then be crumbled with the attack, seen above all by the childish eyes of the youngest son. But the childish drama in the film is lost with its rather faded outlines, which changes and loses tone continuously throughout the narrative. The most complex visual and narrative knot is the attention with which the director focuses almost obsessively on the face of the young Garaci, who is too young, and the continuous widening and tightening of the frame becomes pressing, a directing game that the actor is unable to sustain with his performance. It's as if the director wanted to make the emotions explode, that shock dormant under the skin, but it's a failed effort that leads to a feeling of great asphyxia.

Noce focuses on the externalization of the trauma experienced by mixing together memories, imagination and reality, constantly exchanging the order of these factors that weigh the film down, but siphoning off the only thing that would really make sense of the film, perhaps for a legitimate personal modesty: feeling.

Padrenostro will be in theaters from September 24, 2020.

The afternoon screenings featured another film in competition. It is The Disciple directed by Chaitanya Tamhane, well known in Venice for having already won the Horizons section in 2014 with Court and having collaborated with Alfonso Cuaròn in Rome, Golden Lion of 2018. This time the young Indian director brings to the screens of the Lido a story of cultural tradition that is in danger of becoming extinct due to the raging laws of the contemporary market: a journey along the notes of Indian music chasing each other through the streets of a busy and modern Mumbai, where the protagonist is a true hero of cultural resilience. Sharad Nerulkar spends most of his life being a disciple in the obstinate search for perfection that can make him the musician par excellence. Music is the classical music of North India which is defined "a road to the divine" made not only of notes and staves, voices and musical instruments, but of a real modus operandi necessary to sing and play it. First started by his father and then followed by an old master, Sharad becomes a true symbol of obstinacy and tenacity, passion and discipline in order to reach higher and higher levels. For this reason he completely cancels his life, since he was a child, giving up games with his companions to pursue his dream, and as a young man giving up love and friendship, letting his life pass systematically between exercises and performances. Music is his only way of life, Sharad knows no others and does not want to change even when his health falters.

The search for this perfection satisfies him, at least it seems, and allows him to penetrate into the deepest depths of the mysteries and sacred rituals of the musical legends of his country's past, which create a sort of bubble around him. But each bubble is unstable and fragile and as time passes, it explodes and the disciple is thus forced to confront the complex reality that surrounds him, both of his city and of the path taken until that moment: what was the use of so many sacrifices and so many renunciations? Have they really served any purpose? For him, these questions are like a shock that will violently awaken him, making him walk a new path, that of the life he had renounced: "Faith is the key word for most of those who practice this music. Faith is what drives them to dedicate their entire sight to mastering this complex art. But then there is life and its happenings", said the director.

The film takes us straight to the heart of traditional Indian culture, allowing us to learn about its customs, a history of ancient music, far from the more famous Bollywood, leaving us with a deep reflection on how that sort of coarseness of the present is dramatically able to dampen the reflections on art and attack the foundations of the traditional culture of a country, whatever it may be.

Split criticism on film. For some people, the film is beautiful, while others reproach an excessive slowness of the initial part, which on the one hand is a good connotation of the rhythms of oriental life, but on the other is continually disconnected from the narrative by the presence of the many concerts that do not allow the viewer to delve into the story, lengthening the length of the film unnecessarily.

There are two interesting films among those chosen for the Out of Competition section.

"How do we discover the moment when we become accomplices in a crime, however small? Is there a limit to personal responsibility in cases like this?"

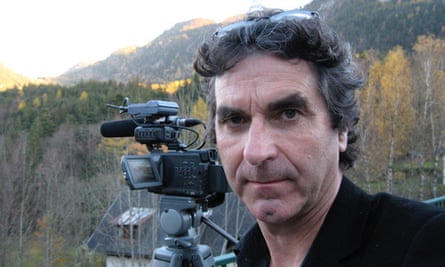

These are the questions that director Luke Holland asks himself in the documentary Final Account.

More than 10 years of interviews, stories and questions to those who during the darkest period of history were on the other side: the Germans. Holland's film is not a simple film about the Holocaust that tells the drama of the Jews, but a completely new look at those people who consciously or unconsciously contributed to the implementation of Hitler's terrible plan. In this decade, the director speaks with more than 300 Germans, eyewitnesses to the horror: war veterans, members of the SS, children who were initiated into Nazism by their families and have now become grandparents, ordinary citizens, workers in charge of carrying out the projects in which the genocides would later take place, soldiers and silent guardians who were all guilty of the factory of death that was "the final solution". A temporal excursus that goes from the first post-war period to Hitler's rise, up to the birth of the National Socialist Party and the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Dachau where Jews were erased from history, and which aims to understand what the Germans knew well that they were not in power. Was it really possible not to know what was being perpetrated against an entire lineage? Today, these men and women called to remember by Holland are dealing with their own conscience, concealing all that horror in voluntary oblivion, in the rejection of a reality or in the minimization of history in order to escape what is a great historical responsibility: is this perhaps the easiest way to survive such a heavy sense of guilt? Is this how one justifies oneself for not having stopped murderous hands? But if on the one hand there are the deniers, on the other hand there are those who feel the sense of guilt as a boulder on their conscience and in life they have never found peace, nor forgiveness towards themselves.

But are you really guilty despite not having stained your hands with the blood of others? Or vice versa can one consider oneself innocent for this?

Guilty or not, the fact is that to accept passively meant to play a decisive role in the genocide: Hitler could never have done everything on his own. Alone he was powerless. It is always the union that makes the strength!

Holland's docu-film is really well done, lucid and simple in its hardness, direct and without much frills and assembly machineries. It manages to keep the viewer's attention high, it never expires in the rhetoric that could be easy in these cases, not even when in the finale it pays homage to the victims, giving image to the stories.

This work is unfortunately posthumous because Luke Holland disappeared last June. He bequeathed us this necessary documentary, of important expressive urgency, a punch to the stomach.

With The Duke, director Roger Michell brings to the big screen an old absurd but true story of the London of the Sixties, a city where the condition of the working class was rather unstable and the elderly did not receive the proper assistance they deserved. In this climate Kempton Bunton is a middle-aged taxi driver torn by grief over the loss of his beloved daughter, who would like to reinvent herself as a writer but who becomes a symbol of struggles and social campaigns. An apparently mild man who becomes the protagonist of a sensational event: he manages to steal the Portrait of the Duke of Wellington, a famous work by Francisco Goya, the first and only case of theft that has ever affected the prestigious London gallery. The man exploited this incredible gesture to blackmail the Government, to which he promised to return the precious work only on condition that it would improve the condition of the elderly by offering them support and services hitherto denied. The film stars two Oscar winners: Jim Broadbent in the taxi driver's loaves and Helen Mirren in those of his wife exhausted by the intemperance of her husband who, as a meek man, decides to face the highest power of society.

The story of this theft is incredibly true, but has been shrouded in mystery for 50 years, until the Bunton family chose to tell the truth to the film's producers.

The director says that "The Duke is part of the great tradition of "healing comedies" - comedies that make you feel good - which in this case show a simple man who finds himself talking openly to the powerful. However, this is still a little known story, but very famous in its time. Bunton is on the one hand a peculiar Robin Hood and, on the other, a little man who at a certain point has the opportunity to raise his voice in front of the powerful. In English culture there is a celebration of these eccentric types".

See you tomorrow with Day 4 of this Venice77.

Lascia un commento