It may seem paradoxical but the city of Venice has always had considerable difficulties in supplying drinking water. As the Venetian historian and chronicler Marin Sanudo wrote "Venice is in water and has no water", because the Serenissima lacked branches of fresh water, present only at the Lido, where the discovery of wells formed thanks to the accumulation of rainwater then filtered by layers of sand was the basis of the construction of the Venetian style wells. The supply of drinking water was vital and the authorities immediately promoted with great energy the initiative of private citizens, especially those of the noble branch, because they were structurally complex and economically demanding constructions: the well was built and then donated to the city, thus also giving prestige to the family. In the first years of 1300 the Maggior Consiglio ordered the construction of about 50 wells and it was so important that after only ten years, in 1386, the Corporazione degli Acquaioli was established, which dealt with the matter specifically, to which were then added 3 magistracies: the Municipal Procurators to whom was entrusted the task of supervising the construction and maintenance works, the Magistrate of Water that instead supervised the artificial canal of the river Brenta from which water was drawn in case of drought, and the Magistrate of Healthcare for the important sanitary aspect. The sanitary aspect, therefore, was of fundamental importance, and in addition to these public corporations, also the parish priests and the heads of the trade were entrusted with the operations of surveillance and above all with the custody of the wells: they were the ones who kept the keys, because the wells were not always open, but the access and withdrawal of water was allowed only twice a day, in the morning and in the evening, when the bell of the wells rang.

The well built in this way was closed with a stone element, called in Venetian jargon "vera da pozzo", and this is what we see in underground wells: born as a simple closing element, over time they became small works of art, ornamenting fields and courtyards.

The realization of these particular structures continued also in the following centuries: around the middle of the 19th century the Municipal Technical Office of Venice recorded 6046 private wells, while there were only 180 public wells. After a few years, however, with the completion of the public aqueduct, this centuries-old tradition was interrupted: the old wells gradually went into disuse, and many of them were even paired with metal or cement structures.

How wells were built in Venice

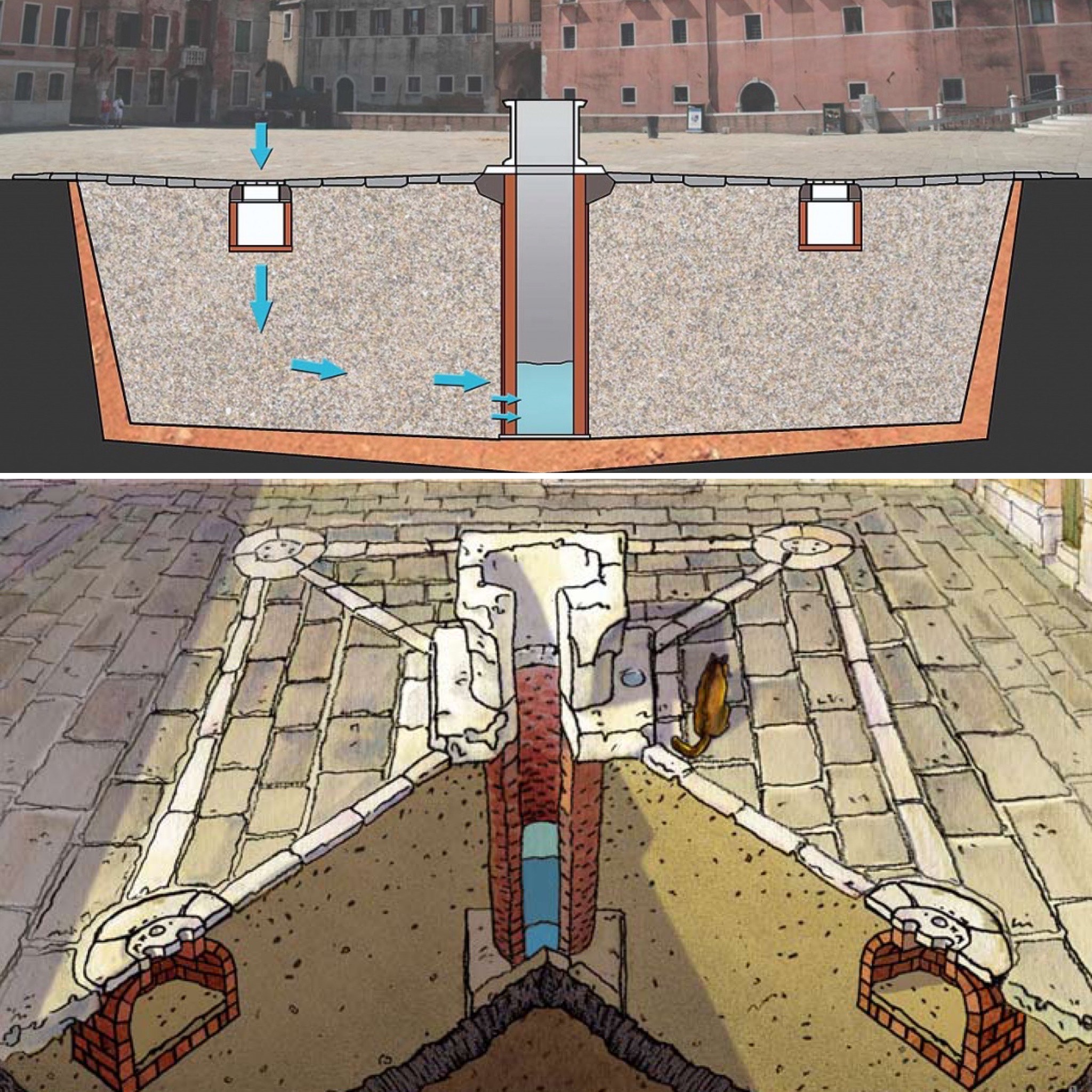

Having clarified that it was very difficult to find drinking water in the city of Venice, the construction of a well remained the only possible solution. Usually, elsewhere, the classic artesian wells that had direct access to an underground spring were built. But in the Lagoon, because of the lack of fresh water, rainwater had to be somehow exploited. This factor profoundly influenced the construction of the Venetian style wells: in fact, it was an indispensable condition that around the well there was a large collection area where rainwater could flow, and therefore accumulate. This is why the construction took place mostly in fields and courtyards, often of considerable size. But not all areas had a natural impluvium and therefore sometimes it was necessary to raise the area concerned, as is easy to see in Campo Sant'Angelo, or in Campo della Chiesa di San Trovaso, or in Piazzetta dei Leoncini di San Marco.

Once the suitable area had been chosen, it was dug for about six metres: the tunnel was covered with a blanket of waterproof clay and then filled with layers of sand with the function of a filter. The rainwater was collected through the so-called pilelle, manholes made of Istrian stone placed symmetrically to the shaft. The well pipe, on the other hand, was placed in the centre of the chosen area: it was placed on a disc-shaped structure made of Istrian stone, and built with specific bricks called pozzali. The upper part of the well, the external part, was the so-called vera, often built with Istrian stone and embellished with decorations of high artistic value. Its function was twofold: to avoid the accidental fall of people and objects inside the well and to act as a support for those who drew water, making the operation easier. As the centuries went by, the decoration of the real ones became more and more articulated, assuming the role of real small works of art: often they were made with archaeological bare material, such as the capitals of ancient Roman buildings, or enriched with elements inspired by nature such as plants, flowers and fruit, or even with animals with a proud character such as peacocks and lions, but also with cherubs and angels. Almost all of the ornaments bore the coat of arms or weapon of the family that had built the well, as a connotative and recognizable element. The final touch was represented by the masegni of the paving, which connected the well to the field or square chosen for its construction.

The vere da pozzo as real works of art

Today there are about 600 Venetian wells that have survived the advent of modernity. Deprived of their fundamental public function, they remain a living testimony of Venetian urban and artistic history, especially for the high value of their decorations, the vere from late-medieval Latin viria, bracelet, or in technical jargon puteali or ghiere, are in some cases authentic works of art, and deserve to be counted among those unmissable monuments that characterize exclusively the city of Venice.

But what are the main real well paintings that you can still admire today? Here is a short list:

- in the Cà d'Oro on the Grand Canal, the splendid red marble from Verona in 1427 by Bartolomeo Bon;

- in the inner courtyard of Palazzo Ducale the two masterpieces in bronze created respectively by Nicolò dei Conti in 1556 and by Alfonso Alberghetti by 1559;

- at the Museo Correr, an early Christian example dating back to the 5th century, an example of "archaeological recovery";

- in Campo San Giovanni e Paolo, a real circular, from the early 16th century made of Istrian stone, here moved from Palazzo Corner in San Maurizio in 1824;

- in Campo Santa Maria Formosa the real cylindrical stone from Istria dated 1755, coeval with the restoration of the two public ;

- in Campo Santo Stefano, the real Istrian stone circular made in 1724;

- in the cloister of Sant'Apollonia, the cubic sail decorated with amphorae, of uncertain ;

- in Campo dell'Angelo Raffaele, the sail built in 1349 as an ex-voto of the Ariani family for the plague of 1348;

- in Piazzetta dei Leoncini di San Marco, the only well in the entire Marciana area.

The others await you in the streets of Venice, in the fields, in the cloisters, silent witnesses of the long and glorious history of the Serenissima.

Have fun finding them...

Lascia un commento